THE FORGOTTEN

Mental Illness in Africa and Italy

The emotions that the mentally ill experience are splinters of an indecipherable world for them, and each sensation enters the rooms of their minds, disconnects reality and takes its own path, made up of many small intersecting spheres.

“The Forgotten Ones” is a journey to the brink of madness, to the universe of Italian and African psychiatry, to the human search for what madness is: the gestures, the looks, the time of those who struggle to live the emotional and fast pace of reality.

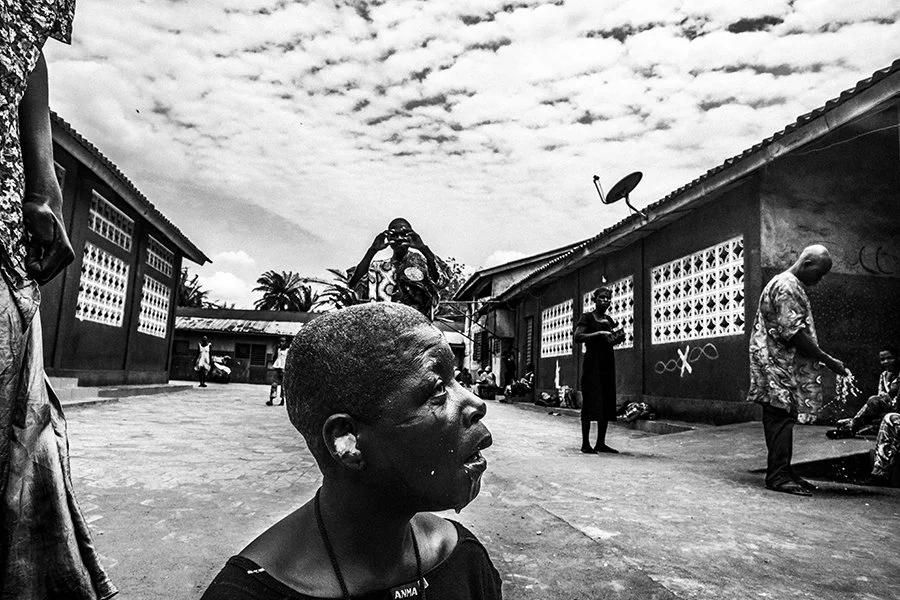

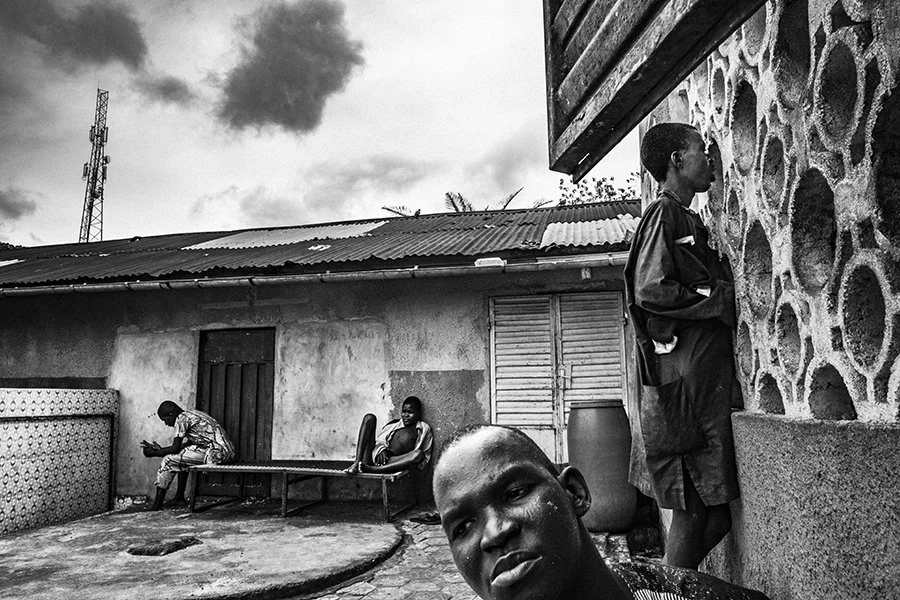

Being able to decipher the process of those who are mentally ill is a complex thing, because madness is not one and the same and is not reflected in a single image, but has a thousand different forms that bounce from person to person and grab the unconscious by the tail making them shut up or scream, or simply whisper a language that is often foreign to those around them. Sick people need different care and attention because their perceptions constantly change and make the “voices” they hear change from time to time or throughout the day. My photo reportage started by observing. Before I started photographing, I was not taking pictures but trying to decipher the space and time of those who sat for hours staring into space and those who moved frantically without stopping talking. In Africa I encountered the power and strength of Grégoire, a kind of black Basaglia, who dedicated his entire life to recognizing the mentally ill as a person.

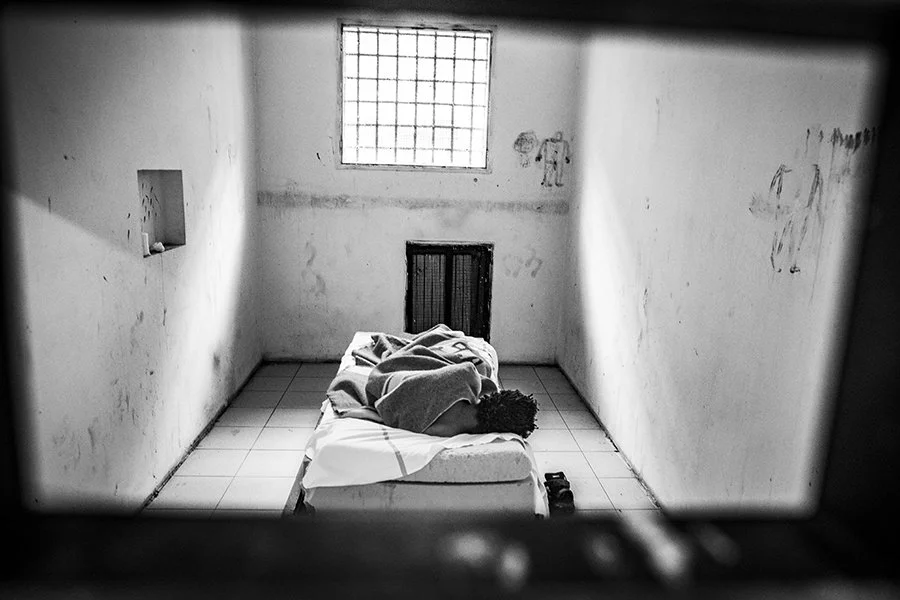

He thus managed to save a man lying in a dusty hole on a road in Togo and take him to one of the centers he founded for abandoned psychiatric patients. Here, men reduced to skin and bones, devoured by time and emotional scars, have the opportunity to recognize themselves, to not be at the mercy of their interior spaces. I tried to immortalize the fixed gaze of the patients that echoed in the colored silence of their rooms where they remained immobile, in a sort of imaginary interior embrace. But mental illness in Africa is also that of the psychiatric hospitals in Zambia, where I saw men bent and paralyzed for hours without moving, or that of the streets of Nairobi where the mentally ill scream and curl up lying down near the market.

In Italy I have visited all the centers that welcome psychiatric patients: from SPDC to REMS where those who have committed crimes are locked up, passing through communities, clinics, family homes and the actual prison. A world made of small things, of attention and silence, but also of many daily difficulties to overcome. The story of mental illness has thus become another chapter in my constant research on the invisible world that I have been carrying out for over twenty years: an anthropological investigation into the lost freedom of those locked up in prison, of those who use drugs, of those who are deaf and now of those who have a psychiatric problem.